The other day, I heard an idea I haven’t been able to put down: that we’re entering the era of the career generalist.

While I’m not personally here to prophecize about the future for generalists, the argument goes something like this: because businesses are tackling a rapid rate of change in the world, it is becoming increasingly harder to pinpoint particular skills, package them into particular jobs, and create enduring roles that will stand the test of AI-accelerated time. Simultaneously, sharp critical thinkers, good communicators, and change-adept, shape-shifting professionals are becoming more attractive as employees because they are likely to be able to navigate an ambiguous future.

Whether the time for us generalists has come or not, this idea has got me thinking a lot about what it means to be a generalist—an exceptional one in particular. And while I won’t pretend to be the world’s most skilled generalist, I do know a thing or two about succeeding as a skilled but unspecialized professional.

Since much of the essential advice about being a generalist (e.g., work on your communication skills) is obvious, I’m not going to bore you with it. You can consult ChatGPT. But over the past eight years of changing industries, roles, functions, and focus areas on at least an annual basis, I’ve learned a few hard-earned lessons about what exceptional generalists have in their toolkits that others don’t.

So, in case we are headed into the era of the career generalist, here are some recommendations for what you need—and maybe haven’t thought about—to succeed in a winding and undefined career.

The Advanced Generalist’s Tookit

Tool No. 1 | A Self Awareness System

One of the first and most important things I learned about being a generalist is that contrary to the idea that you are qualified to do almost anything, you are, in fact, underqualified to do almost everything. Sometimes, that lack of qualification really matters, and often it really doesn’t. Many tasks can be accomplished with resourcefulness, commitment, and good common sense.

But crucially, some can’t.

Knowing what you can and can’t do is essential when you’re a generalist. It prevents you from taking on work you are unequipped to succeed and also prevents you from turning down work out of fear instead of reasonable judgment. However, the mistake I learned that most people are making is assuming that they are capable of knowing what they can and can’t do on their own. Scientifically… we’re not so good at that.

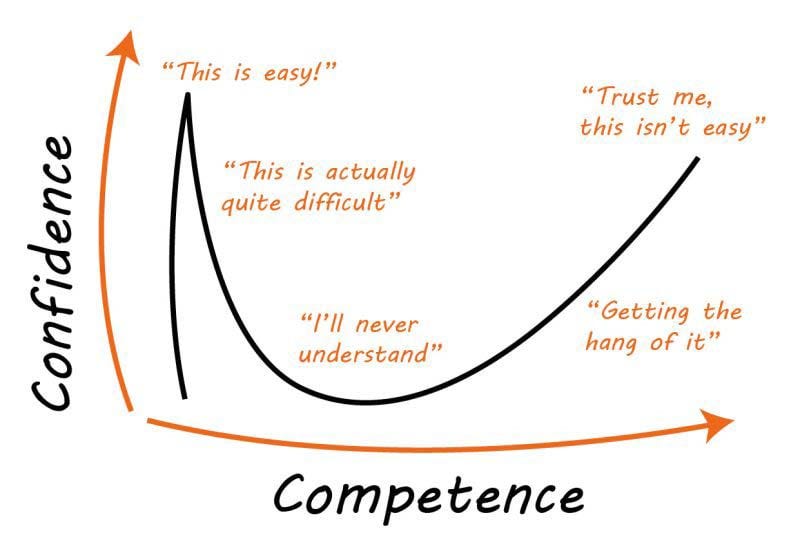

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect, but if you haven’t, all you need to know is that we’re horrifically bad at estimating our skills. In particular, we’re bad at realizing how little we know when we know just enough to be dangerous. While someone who has never attempted something may appreciate how unskilled they are, the second we get a bit of knowledge and experience under our belts, we’re quick to overestimate our capabilities and think that things are easier than they are.

While we’re all susceptible to this cognitive bias, I would argue generalists are uniquely at risk. If your career is built on the belief that you always “figure it out” when you’re smart but unknowledgeable, you likely live in a heightened world of overconfidence with some major blind spots about what you can and can’t do. Though it is always worthwhile to work on building self-awareness, it’s important for generalists to rely on checks and balances that go beyond their own self-assessments.

This is what I call a Self-Awareness System: the set of people, practices, and safeguards you put in place to ensure you’re signing up for work you’re capable of succeeding at and saying no to things that can tank your credibility or relationships.

For me, that system has multiple components. The most important ones are trusted people in my life who will tell me if I’m biting off more than I can chew (pro tip: boyfriends who think you’re the sun and the moon are not to be included) and questions I can ask myself to check my own self-confidence. Some of those questions include:

What’s the difference between doing a good and a great job at this task?

If it were my job to hire someone to do this work instead of doing it myself, what would be the profile of the person I’d hire? Do I fit that profile?

Can I name at least 5 of my experiences that I’m confident will be relevant to this task?

Can I find proof of how long and how resource-intensive it is to build the skills to do this work (i.e., am I trying to do a thing people get degrees in or something that most people tackle after a 2-week online course)

This is an imperfect and incomplete list of questions, but it’s part of a system that prevents me from signing up for things when I’m not the right person for the job. Regardless of which people and reality checks you set up, adding a few steps to challenge your overconfidence can be immensely helpful.

Tool No. 2 | A Robust Network of Specialists

Once you’ve built yourself a system for figuring out when you’re the wrong person for the job, the next thing you need to excel as a generalist is a lot of connections to people you trust who are likely to be the right person. You need a network of specialists.

As a generalist, specialists are your best friends. They can be part of your Self Awareness System by providing you with counsel and expert opinions, and they can also enable you to add value in situations where people need help that you can’t directly provide. Whole economies are built on the skill of connecting the right people to the right work, and by developing a network of highly skilled specialists whom you can connect to opportunities, you will grow your own utility as a connector and resource to others.

I will now acknowledge the pain, awkwardness, and discomfort of building a network—particularly one that’s full of people with different interests, skills, and qualities than your own. For most of my life, I have hated networking. Even thinking about it made me feel like I didn’t know what to do with my hands. However, in the past year, I’ve spent a lot of time working on how to get over my fear of networking, and if you’re resistant or fearful in the face of the suggestion to build your network, here’s the reframing that converted me.

Unlike people who dive into well-trodden, linear career paths, generalists often wander through their professional lives with alarmingly little certainty. While it’s always likely that you’ll be needed to do something, it is never promised. And when your job is to be a dynamic peg that can fit into a weird hexagon-shaped hole that no one else was quite cut out for, you’re only useful as long as that hole still needs to be filled. However, the upside of tolerating that ambiguity is that every oddly-shaped business need is an opportunity for advancement. And, in my experience, that often means that career opportunities come at you quickly and in more significant volumes. Put plainly, a skilled generalist is positioned to get more opportunities than others.

What changed my orientation to networking was the realization that if I go at every opportunity alone, I am monopolizing the benefit of that constant stream of opportunity and the breadth of situations I’m exposed to. If I go at it with a network of people who might be the perfectly shaped piece for any of the wide assortment of puzzles I’m exposed to, I can spread that benefit to others. Networking, while mutually beneficial, doesn’t have to be about you. It can be about finding awesome people you want to promote and champion and knowing that you are in a unique position to support people whose careers do not expose them to breadth.

That reframe changed everything for me. I feel no awkwardness reaching out to an engineer or graphic designer and saying, “Hey, I keep getting asked if I know any designers, and I am trying to build some relationships so I can be a better connector -- I saw your work and would love to learn more about you, your aspirations, and if you might be a good person to introduce my colleague to!” It’s just an infinitely easy message to send.

And while I’ve got a whole different newsletter in me on how I started to network in ways that felt safe and authentic to me (Slack communities, not happy hours!!!), the thing that matters as you consider your career as a generalist is building relationships where you can bring people along for the perks of your journey while also increasing your own value.

Tool No. 3 | A Strong Personal Brand

The last thing that every high-skilled generalist needs to stand out is a clear and strong personal brand. And before you recoil at the idea that I’m asking you to build up your LinkedIn following — I’m not. When I say personal brand, I mean you need a consistent and clear reputation to help people understand how to best prioritize and utilize your time.

Without a strong brand, you risk spending your whole career trapped in the land of tasks that I call “useful but not valuable,” particularly if you're a woman or minority in the workplace.

Planning your team’s happy hour because there’s no designated admin, but you’re good with logistics… useful but not valuable. Always taking notes in the meeting because you’re proactive and organized… useful but not valuable. Making slides, organizing file architectures, picking up odds-and-ends tasks, and teaching people how to use the printer are all undeniably useful. But if you want to build a career that allows you to lead, make decisions, influence others, and have an outsized impact, being useful is not in your best interest.

This is the generalist’s trap: that at your core, you are deeply useful and also uniquely likely to say “yes” to doing things others won’t because the breadth of experience is key to your growth. That almost inevitably makes your default brand “useful and eager,” where others benefit from the implicit branding of being associated with a skill (don’t pretend you don’t associate brands with being a software engineer or a private equity analyst), being just “useful and eager” will leave you trapped in cycles of doing work that is unlikely to help you grow.

Quick caveat: I want to be clear that administrative work is valuable work. But being an admin is a skill and a discipline, and if your goal is not to have an administrative job, doing rogue administrative tasks is not valuable to your career. Career admins: you’re my favorite people—carry on. Generalists who don’t see a career in administrative roles, I’m talking to you.

I struggled for years (and still struggle) with escaping the trap of being too useful to be valuable. What helped me most, beyond just plain old getting older, was building a personal brand that helped people around me understand what types of tasks I’m great at vs. good at, what my goals are, and where I’m uniquely cut out to add value.

Building that brand takes intention, and I recommend on focusing on three parts of it:

What you value and stand for

What you’re better at than 90% of people

What your goals are

Communicating these things to people through your words, actions, and decisions can help ensure others are selective about how they ask for your time, and it can help you be selective about how you give it. Knowing what you want your personal brand to be and making choices in alignment will help you focus on jobs and projects that can ladder into a more cohesive career while also making it easier for others to help you do the same.

So if your resume looks like a collage instead of a career path, think about what you can do across all aspects of your professional life to help people make sense of who you are and what you’re about. Over time, as people understand that brand more clearly, throwing random tasks at you will feel less appropriate because your skillset isn’t just “misc.”

Best of luck tackling a wide range of ambiguously scoped tasks.

Thanks—always—for reading.

So insightful and thought provoking. Thanks for sharing timely suggestions for the current evolving workplace. Much respect! Melissa Wade